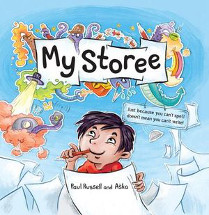

My Storee by Paul Russell and Aska

EK Books, 2018. ISBN 9781925335774

(Age: 5-8) When he is at home the stories running through his head

keep him awake at night - stories about dragons and rainbow eggs at

the bottom of Grandma's garden; his teacher being eaten by a

gruesome ogre; unicorn detectives chasing robotic pirates up alien

volcanoes. The wonderful, magical ideas just keep flowing and he

writes and writes and writes. It's all about the adventures and not

about the writing rules.

But at school, the adventures dry up because the writing rules rule.

And the red pen is everywhere,

"But at school their are too many riting rulz and with all the rulz

I can never find my dragons."

At school he doesn't like to write

Until a new teacher comes - one who is a storyteller himself and

knows writing is about the story and not the rules.

In the 80s I was lucky enough to be deeply involved in the process

writing movement where we truly believed that writing had to be

about the ideas and the adventures and that the processes of

reviewing, editing and publishing came later once there was

something to work with. Children were just happy to express

themselves and as teachers, it was our job to guide them with

spelling, punctuation and grammar, semantics and syntax, so that if

one of their ideas grabbed them enough that they wanted to take it

through to publication then we would work together to do that. Words

were provided as they were needed in context, and punctuation and

grammar tackled on an individual's needs rather than

one-size-fits-all lessons. And if the effort of writing was enough

and the child wasn't interested in taking it further, then we had to

accept that - flogging a dead horse was a waste of time. In

pre-computer days, how many nights did I spend on the typewriter

with the big font so a child could have the joy of their own

creation in our class library? Children enjoyed writing for

writing's sake, were free and willing to let their imaginations roam

free and were prepared to take risks with language conventions for

the sake of the story.

But when publicity-seeking politicians whose only experience with

the classroom was their own decades previously declared that

"assessment processes need to be more rigorous, more standardised

and more professional" (a quote from "Teacher") we find ourselves

back to the red pen being king and our future storytellers silenced

through fear. While the teachers' notes tag this book as being about

a dyslexic child, it really is about all children as they learn how

to control their squiggles and regiment them into acceptable

combinations so they make sense to others, a developmental process

that evolves as they read and write rather than having a particular

issue that is easy and quick to label and therefore blame. We need

to accept what they offer us as they make this journey and if they

never quite reach the destination, or are, indeed, dyslexic, then as

well-known dyslexic Jackie French says, "That's what spellcheck and

other people are for." So much better to appreciate their effort

than never have the pleasure of their stories.

So many children will relate to this story - those whose mums have

"to wade through a papar ocean to wake [them] up" - and will

continue to keep writing regardless of adults who think they know

better. But who among those adults will have the conviction and the

courage to be like Mr Watson? Who among the powers-that-be will let

them do what they know works best? If the red pen kills their

creativity now, where will the storytellers and imaginative

problem-solvers of the future come from?

Barbara Braxton