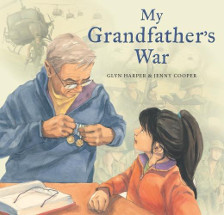

My grandfather's war by Glynn Harper

Ill. by Jenny Cooper. EK Books, 2018. ISBN 9781775592990

My grandfather's war tells us of a more recent conflict, the Vietnam

War, a war where those who served are now the grandparents of its

target audience, our primary school students.

At a time when the world had almost emerged into a new era following

World War II, the USA and the USSR were the new superpowers and the

common catch-cry promoted by prime ministers and politicians was

"All the way with LBJ", Australian and New Zealand joined forces

with the USA in this new conflict to stop the "Yellow Peril" of

China moving south and overtaking nations just as Japan had tried to

do between 1941 and 1945. Among the 65 000 troops of both nations

committed between 1963 and 1975 was Robert, Sarah's grandfather who

now lives with her family and who is "sometimes very sad."

Possibly a natio, drafted because a marble with his birthdate on it

dropped into a bucket, old enough to die for his country but too

young to vote for those who sent him, Robert, like so many others of

his age whose fathers and grandfathers had served, thought that this

was his turn and his duty and that the war "would be exciting". But

this was a war unlike those fought by the conservative, traditional

decision-makers - this was one fought in jungles and villages where

the enemy could be anywhere and anyone; one where chemicals were

used almost as much as bullets; one where the soldiers were not

welcomed as liberators but as invaders; and one which the soldiers

themselves knew they could not win. It was also the first war that

was taken directly into the lounge rooms of those at home as

television became more widespread, affordable and accessible.

And the reality of the images shown clashed with the ideality of

those watching them, a "make-love-not-war" generation who, naive to

the ways of politics and its big-picture perspective of power and

prestige, were more concerned for the individual civilians whose

lives were being destroyed and demanded that the troops be

withdrawn. Huge marches were held throughout the USA, New Zealand

and Australia and politicians, recognising that the protesters were

old enough to vote and held their futures in their hands, began the

withdrawal.

But this was not the triumphant homecoming like those of the

servicemen before them. Robert came home to a hostile nation who

held him and his fellow soldiers personally responsible for the

atrocities they had seen on their screens. There were no welcome

home marches, no public thanks, no acknowledgement of heroes and

heroism, and Robert, like so many of those he fought with, slipped

back into society almost as though he was in disgrace. While the

official statistics record 578 killed and 3187 wounded across the

two countries, the stats for those who continued to suffer from

their physical and mental wounds and those who died because of them,

often at their own hands, are much more difficult to discover. Like

most returned servicemen, Robert did not talk about his experiences,

not wanting to inflict the horror on his family and friends and

believing that unless you were there you wouldn't understand; and

without the acknowledgement and support of the nation he was

supposedly saving and seeing his mates continue to battle the impact

of both the conflict and the chemicals, he sank into that deep

depression that Sarah sees as his sadness but which is now known as

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Disturbed by his sadness but told never to talk to her grandfather

about the war, Sarah is curious and turns to the library for help.

But with her questions unanswered there, she finally plucks up the

courage to ask him and then she learns Grandad's story - a story

that could be told to our students by any number of grandfathers,

and one that will raise so many memories as the 50th anniversary of

the Battle of Khe Sanh approaches, and perhaps prompt other Sarahs

to talk to their grandfathers.

Few picture books about the Vietnam War have been written for young

readers, and yet it is a period of our history that is perhaps

having the greatest impact on our nation and its families in current

times. Apart from the personal impact on families as grandfathers,

particularly, continue to struggle with their demons, it opened the

gates to Asian immigration in an unprecedented way, changing and

shaping our nation permanently.

Together, Harper and Cooper have created a sensitive, personal and

accessible story that needs to be shared, its origins explored and

understanding generated.

Lest We Forget.

Barbara Braxton