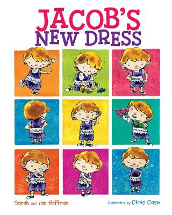

Jacob's new dress by Sarah and Ian Hoffman

Ill. by Chris Case. Albert Whitman, 2014. ISBN 9780807563731.

There are many costumes to choose from in the class dress-up corner

- firemen, dragons, farmers, knights in shining armour - but Jacob

insists on wearing the princess dress complete with crown. Even when

Ms Wilson suggests alternatives to deflect the derision he is

receiving, particularly from Christopher, he proudly informs her

that he is the princess. At home that afternoon, his mother

reaffirms that boys can wear dresses and even suggests he plays in

his Hallowe'en witch's outfit but when he proposes to wear it to

school the next day she is caught in a dilemma of acknowledging her

son's choices and protecting him for the cruelty of his classmates.

When Jacob creates an alternative - a toga-like outfit he makes from

towels - she is happier, especially when Jacob agrees to wear shorts

and a shirt underneath.

However, while his friend Emily admires his creation, that is not

enough for Christopher and the rest of the boys who cannot deal with

Jacob's nonconformist persona and Jacob goes home miserable and

confused, but determined. He asks his mother to make him a real

dress but she hesitates, and the longer she hesitates the harder it

is for Jacob to breathe. Will his mum support what for him is a

natural expression of who he is, or will she try to protect him from

the Christophers of the world?

Just ten years ago, there was a 'Jacob' at the school where I taught

- a young lad who preferred the princess outfits, made long hair

from plaited pantyhose, and whose choices made him not only the butt

of the playground bullies but also the subject of many

teacher-parent and teacher-teacher conferences as we tried to find a

way through the minefield that saw him become more and more anxious

and isolated as he progressed through the years. Gender identity

issues were not common - in fact, our Jacob was the first gender

nonconforming child that many of us had taught. In hindsight and

with what we know now, his dependence in other areas was just a

manifestation of his insecurity and need to be acknowledged like a

regular child, that he was more than his gender confusion and we

needed to look harder beneath the outer to seek the inner. How

welcome a book like Jacob's New Dress would have been to

give us some guidance, for like Jacob's parents in the story,

teachers too are trapped in the dilemma of acknowledgement and

protection. Ms Wilson tells her class that Jacob wears what he's

comfortable in. Just like you do. Not very long ago little girls

couldn't wear pants. Can you imagine that?" If we don't make

judgements about a girl's future sexuality because she prefers to

wear blue jeans and to play football, why do we react so strongly to

a boy making alternative choices?

This story was born of the authors' own experience with their own

child and while there are many unanswered questions about both the

cause of and the future for such children, the strong message is

that 'support and acceptance from family, peers and community make a

huge difference in the future health and mental health of these

kids'. Just like any child, really. Ms Wilson is a role model for

teachers - gender nonconformity is just another way of being

different and 'there are many ways to be boys [and girls].' Just a

couple of generations ago people who were left-handed often had the

offending hand ties behind their back to compel them to write with

their right - perhaps it won't be too long before 'pink boys' are as

accepted as lefties are today. Perhaps we could start the

conversations with questions such as:

If Jacob were in our class, are you more likely to be like Emily or

Christopher?

How would you feel if someone made fun of you wearing your favourite

clothes or wouldn't let you wear them?

Has that happened to you? Do you want to share?

Why do you think Christopher reacts the way he does?

What did you like/not like about the way Ms Wilson dealt with the

issue?

If you were Jacob's mum or dad, what decision would you make?

Apart from anything else, an astute teacher will pick up on any

sexism issues that might be bubbling below the surface.

However, there is another level to this book. While, on the surface,

this appears to be a picture book for the young (the recommended age

is 4-7) it would also be a brilliant springboard to a study about

what is masculine and what is feminine and the messages portrayed

through the media about what is valued about and for each; the

relationship between the clothes we wear and our perceived position

in society; and whether, despite the feminist movement, whether

deep-down core values and beliefs have really changed. Are

gender-based stereotypes perpetuated? In the vein of Tomie dePaola's

Oliver Button is a Sissy this is yet another example of a

picture book (usually seen as the reading realm of the very young)

actually having an audience of all ages.

Barbara Braxton